The 30 January Environment Bill 2020 Policy Paper repeats the mantra of Theresa May’s ’25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment’ (2018) about having a metric to determine quite how biodiversity enhancement can be measured. The new Environment Bill 2020, through Michael Gove’s continuing encouragement ‘introduces a mandatory requirement for biodiversity net gain in the planning system, to ensure that new developments enhance biodiversity and create new green spaces for local communities to enjoy.’ England will benefit from the saving of £1.4 billion of ‘annual natural capital benefits’ representing ‘several thousands of hectare of habitat’ that will not now be lost! Ecosystems will benefit (e.g. air pollution, water flow control…) but they do not mention conservation of soils which is a significant issue in some protected areas such as AONBs. The bill states that the metric system will not undermine the existing range of protections that exists, not least of all ‘irreplaceable habitats’ and protected sites. That is fine then. ‘Conserve and enhance’ is fundamental to all UK conservation law, and it pops up again in the Environment Bill as ‘enhance and conserve biodiversity’ and helping to ‘deliver thriving natural spaces for communities.’ Communities is an issue that gets greater attention here. We are reminded that NERC (2006) originally set out a duty on public bodies to ‘have regard’ to conserving biodiversity, and the new bill seeks to strengthen LPAs in effecting ‘meaningful change.’ LPAs need to look out as they will have to return a ‘five-year report on the actions taken to comply with the new duty’ (surely updating the NERC 2006 duty of 14 years ago, if they have not done this already?). So two years in from the suggested biodiversity metric, we await much quantitative data proving that the loss of the natural capital has been halted. The Rt Hon Michael Gove would then be very pleased and offer us his big smile of success.

Category Archives: Conservation

Hdbook of Whales…2020

Handbook of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. By Mark Carwardine. Published by Bloomsbury, 2020. 528pp.

The author is the world’s expert on whales, dolphins and porpoises, having already written over 50 wildlife and conservation books. He is also a familiar voice on BBC Radio 4’s Nature programme and has been seen working with Stephen Fry on ‘Last Chance to See’ series. This tome is by far the best, and comprehensive handbook on the group. It is too heavy to go in a field coat, but it will be essential back in the ships’ mess, field laboratory or university library for identification. Mammalogist Carwardine has acknowledged the input of over 70 scientists who have assisted with the field observations to make the book such a colossus of information. Each of the 90 species of cetacean has been meticulously described. Over 1,000 illustrations were commissioned from artists: Martin Camm, Rebecca Robinson and Toni Llobet and the text is also illustrated with colour photographs throughout. The detail for each species is superlative. I could find nothing omitted – annotated diagrams describing all the external features of each sex, colour variants, identification from photos, population differences, similar species, distribution, maps, teeth, behaviour, predators, populations, conservation and vocalisations. This is just a fascinating book for all naturalists, even if you are not a whale enthusiast, it is a gazetteer of cetaceans; I only wish I had read up from this book about the pink river dolphins before I met them in the Amazon. Then I would have been much wiser. John Feltwell.

Global Warming – Amazon

Climate Change & British Wildlife 2018

Climate Change and British Wildlife by Trevor Beebee. 2018. London, Bloomsbury. 368 pp. £35.00

The author is an emeritus professor at the University of Sussex and is best known for his life time’s work on amphibians. The book is number six in ‘The British Wildlife Collection’, the others being Mushrooms, Meadows, Rivers, Mountain Flowers and Saltmarsh. They have the feel of newer volumes in the New Naturalists books by Collins in size, length and colour illustrations. The book has ten chapters and deals with habitats and groups of flora and fauna. Although the evidence is not always clear cut, the position is held that warmer and wetter winters combined with longer summers have worked for the advantage of plants and a whole range of insects, as a result of climate change. The flyleaf says the book is essential reading for every British naturalist and I would agree. The captions to all the many excellent colour illustrations impart a little snippet of the effect of climate change. There is a section on the scientists who have assisted in bringing the factual information together, from Tim Sparks – ‘the leading phenologist of recent times’, Chris Thomas on trends and ranges of butterflies, James Pearch-Higgins for BTO work and Rachel McCarthy as a climate scientist and poet. And now for the caveats: The greater understanding of what groups of animals are doing is limited by the available data; the author says that for freshwater fishes, reptiles and mammals data deficiencies limits our understanding of their phenology….’for fishes and amphibians there has been limited evidence of climate-related changes either way in terms of distribution and abundance’ (p. 161). For fungi, lichens and microbes in the British countryside the author argues that it is ‘habitat damage and deterioration, including atmospheric and freshwater pollution’ that has dominated the recent fates of these groups (p. 179). He states that much of the UK’s farmland is now a wildlife desert since the Second World War (p. 207) and that ‘generalists’ such as carrion crows, and that only annual plants and insects and perhaps highly mobile birds are likely to survive (p.213). Beebee believes that the kittiwake is the most affected British animal of climate change, and that ‘arguably the most negative effect of climate change anywhere in and around the UK, matched only by the plight of arctic-alpine plants, has been the disruption of North Sea food webs. Acidification and increased carbon dioxide is the problem that affects the marine environment (p.243). As for invertebrates there is a lot of information available that suggests that climate change is beneficial in expanding ranges but considerable doubt it thrown into the discussion…’these complex interactions are disentangled.. ‘all taxonomic groups are declining in the UK as a result of the unrelenting efforts of the agrochemical industry and habitat destruction. Any benefits of climate warming are a minor superimposition on this ongoing disaster.’ This is an excellent book and ideal for all natural history libraries. An Index and References completes the book.

Ancient Woodland Inventory, 2018

Ancient Woodland Inventory, 2018. SANSUM, P. & BANNISTER, N.R. 2018. A Handbook for updating the Ancient Woodland Inventory for England. Natural England Commissioned Reports NECR248 Edition 1. Dated May 2018. 187pp

The original Ancient Woodland Inventory (AW1) was originally published provisionally in 1992 following research dating back to 1981. This current handbook is a working document which is collating evidenced-based information as it becomes available. Much of the research for this has come from the High Weald AONB Unit in East Sussex, the Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre and Natural England. It is not surprising that a lot of the evidence has come from the heavily wooded parts of Southern England which plays host to some of the best ancient woodland in England. Data has also been incorporated from work in Herefordshire and in Dorset and work from the Sheffield Hallam University.

The process of updating the AW1 is in four phases i) capturing boundaries via GIS, ii) cross-referencing with existing data sets of woodland, iii) evidence gathering, and iv) evaluating and recording each polygon. There is much more clarification regarding Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) ‘wood-pasture and parkland’ which they admit had often been left off maps because of ‘their low tree density’. This is a very technical handbook.

Originally wood-pasture was ‘generally omitted’ from the original AWI and ‘understanding of this habitat type is still developing…’(para 3.3.3.3.). However, this update states that ‘Where ancient wood-pastures are identified they should receive the same consideration as other forms of ancient woodland’ (p.9). This document states that it was the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) which declared that ‘wood-pasture and parkland’ was indeed a UK Priority Habitat where it had the characteristics of veteran trees, often as scattered individuals, and a wide range of other tree and shrub species.

Two months before this Handbook was published Natural England published its guidance in March 2018 on Ancient Woodland, ancient trees and veteran trees: protecting them from development ( an update from its 2014 edition) where it specifically states that ‘other distinct forms of ancient woodland are: wood pastures identified as ancient.

Other NE documents describe the other characteristics of wood-pasture as being pollarded trees, a matrix of grassland, many saproxylic invertebrates, and supporting 41% of priority species associated with woodland (as per Natural England’s 2015 (EIN011) Summary of evidence: wood-pasture and parkland).

Overall, this is a useful update on the understanding and interpretation of wood pasture as a continuum habitat with ancient woodland.

Glover Report, Sept 2019

Review of The Glover Report: Landscapes Review, Final Report by Julian Glover, September 2019. 168pp

The author is Julian Glover, an associate editor at the London Evening Standard and has worked as a leader writer at The Guardian and as a Special Advisor to Number 10. His stated aims are to respect two emotions, i) that there is great quality within AONBs and National Parks (NPs) already protected and ii) that these areas are fragile and ‘that nature in them is in crisis as elsewhere, that communities are changing and that many people do not know these places.’

There is not a lot about habitat loss in this Review, more about how these natural assets can be managed. It is fairly dismissive of the way they are run at present, and proposes bringing National Parks (10) and AONBs (34) together as ‘one family of national landscapes, served by a shared National Landscapes Service (NLS). This fits in with the government’s green agenda.

It is thought that the AONB acronym is too ‘cumbersome’ and both AONBs and NPs should now be called ‘National Landscapes’. These landscapes amount to 24.5% of England (44 ‘disparate bodies’) with room to grow? This document is thus an entrée to introduce a new government body.

It is however up to date with the February 2019 NPPF and emphasises paragraph 172 on great weight should be given to conserving and enhancing….AONBs. It goes on to say..,,,”we urge the government to give the strongest emphasis to its commitment to our national landscapes.” “They should not be the place for major intrusive developments unless, as is stated in the NPPF, they are truly in the national interest without any possible alternative locations being available’ (p63).

On biodiversity loss they quote the National Trust who said “We believe that National Parks and AONBs are not currently delivering on their duty in relation to nature”. They think that Management Plans should be strengthened, and ‘given statutory consultee status, encouragement to develop local plans and changes to the National Planning Policy Framework’.

In protecting what is present it refers to the government’s 25 Year Environment Plan (2018) which sets out a clear ambition: “we want to improve the UK’s air and water quality and protect our many threatened plants, trees and wildlife species.”

The report finds that the current purpose of AONBs in relation to ‘natural beauty’, and ‘wildlife’ and ‘conserve and enhance’ do not reflect the wider scientific ideas embodied in ‘biodiversity’, ‘nature’ ‘natural capital’ or ‘ecosystem services’ . These are fairly damning statements.

In an earlier document, Glover cites the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) ‘Putting Nature on the Map (2016), pointing out the recognition of significant ecological, biological, cultural and scenic value by the IUCN as being of national landscape interest and it fits with their ‘Category V’ for the UK.

Regarding access, Glover reminds us that AONBs are now designated under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000, still only have a single purpose, and only in relation to ‘natural beauty’. ‘indeed we want to see walking further supported by national landscapes taking on rights of way management and the National Landscapes Service supporting National Trails. But it feels wrong that many parts of our most beautiful places are off limits to horse riders, water users, cavers, wild campers and so on. We hope that as part of the government’s commitment to connect more people with nature, it will look seriously at whether the levels of open access we have in our most special places are adequate.

The report highlights the exemplary rewilding work on the large Knepp Wildlife Project in West Sussex and as a reflection of the way that wildlife assessments are going its Proposal 2, is The state of nature and natural capital in our national landscapes should be regularly and robustly assessed, informing the priorities for action.

The London Plan 2019

The London Plan July 2019

The London Plan, The Spatial Development Strategy for London consolidated with alterations since 2011. Mayor of London. Published by the Greater London Authority. March 2016. Version updated January 2017. 441pp. Draft London Plan – ‘consolidated changes version’ July 2019 571pp and ‘clean version’ July 2019 455pp.

The emerging London Plan now exists as two versions ‘consolidated’ and ‘clean’ (both July 2019) whilst discussions and debate continue. There are three relevant wildlife and countryside sections, a new Biodiversity policy (7.19 Biodiversity and Access to Nature), and a new policy on ‘Protecting Open Space and Addressing Deficiency’ (7.18) and a Policy 2.18 on ‘Green Infrastructure: the multi-functional network of green and open spaces.’

Biodiversity, enhancements and ecological gains are embodied in para 7.19, as per ‘The Mayor will work with all relevant partners to ensure a proactive approach to the protection, enhancement, creation, promotion and management of biodiversity in support of the Mayor’s Biodiversity Strategy. This means planning for nature from the beginning of the development process and taking opportunities for positive gains for nature through the layout, design and materials of development proposals and appropriate biodiversity action plans.’ Gains are again emphasised in para 5.7.4 as ‘Development proposals should manage impacts on biodiversity and aim to secure net biodiversity gain.’

The London Plan is not firm on seeking ecological gains. Under ‘Policy GG2 Making the best us of land’ is says ‘aiming to secure net biodiversity gains where possible.’ Ecological gains go hand in hand with ecological calculators that some LPAs are now insisting on, so it is a surprise that calculators are not mentioned in the Plan.

Other useful matters include: para 5.7.4 ‘When making new provision, boroughs are encouraged to take into account the Mayor’s broader aims for green infrastructure and the natural environment, including, but not limited to, the creation of new parks and open spaces, the enhancement of existing open spaces and natural environments, and the provision of enhanced links to London’s green infrastructure.’ ……. ‘Amenity provision and environmental enhancements should be encouraged.’

‘Development proposals should manage impacts on biodiversity and aim to secure net biodiversity gain. This should be, and be informed by the best available ecological information Biodiversity enhancement should be considered and addressed from the start of the development process.’

It is good that the London Plan continues to seek protection or UK designated, and EU protected sites, as per ‘protect and enhance London’s open spaces, including the Green Belt, Metropolitan Open Land, designated nature conservation sites and local spaces, and promote the creation of new green infrastructure and urban greening, including aiming to secure net biodiversity gains where possible. ‘Any proposals promoted or brought forward by the London Plan will not adversely affect the integrity of any European site of nature conservation importance.’

High Weald AONB Management Plan 2019-24

The High Weald AONB Management Plan, 2019-2024

Originally printed in 2004, this is the fourth edition, the others being 2009 and 2014. What has happened in the meantime is the release of the new NPPF of July 2018 and the concept of Natural Capital, both of which are included. However, the impact on development of Ashdown Forest being both SPA and SAC is not discussed; SPA is not mentioned in the Plan, or Glossary. Otherwise the Plan sets out well the rest of the legal framework (‘conserve and enhance’ seems to have been written into every legal instrument since the year dot), is good on setting the historical scene for the AONB and is good on setting out its own policies for conservation. ‘Natural Beauty’ we are told has not really been expressly defined, but we know that this is a major theme; it’s all in the name, hopefully. The AONB covers 1,461km2 and in the jurisdiction of 15 councils. We are informed that there are 13,401 ponds in the AONB with an estimated 1,600 supporting Great Crested Newts, and 12,500km of hedgerow and field boundaries. About <3% of the AONB land cover is known as wildflower meadows with an estimated <40% field semi-improved grassland that has potential for enhancement. About 28% of the AONB is ancient woodland representing nearly three times the national average. There are 2,800 parcels of ancient woodland under 2ha and 56km2 of UK BAP ‘wood pasture and parkland’. All these represent a finite resource within the 4th largest of the 46 AONB’s in the UK. The Plan is well illustrated with maps and colour photographs and is available on line too.

Biodiversity Global Assessment May 6th 2019

Biodiversity – Global Assessment May 6th 2019

The 28 authors released their preliminary summary of the Global Assessment on Biodiversity … on 6 May 2019 stating that the final report is expected later this year and will run for 1,500 pages. This multi-authored tome has also had guidance from 19 other experts from their Management Committee. The experts are drawn from several countries around the world so this is an agreed collective response representing the state of the world’s biodiversity. However the countries for which data has come from appears to be restricted to the UK, USA, Trinidad & Tobago, Mexico, Canada, Argentina, Japan, South Africa, Hungary, Venezuela, France, Germany, Netherlands and Philippines. Missing are many countries including Russia, Japan, China, several European countries and Australia.

Key findings – in their words – are

‘Nature across most of the globe has now been significantly altered by multiple human drivers, with the great majority of indicators of ecosystems and biodiversity showing rapid decline.’

‘Habitat Loss and deterioration have reduced global terrestrial habitat integrity by 30%,, thus…ca. 9% of the worlds est., 5.9 million terrestrial species, more than 500,000 species, have insufficient habitat for long-term survival , are committed to extinction with decades, unless their habitats are restored.’

‘Estimated – 8 million animal and plant species (75% of which are insects), around 1 million are threatened with extinction.’

Wetlands: ‘85% of wetlands has been lost.’

Forests: ‘32 million ha of primary or recovering forest were lost between 2010-2015.’

Coral: ‘Approximately half the live coral cover on coral reefs has been lost since the 1870s’

Vertebrates: ‘Human actions have already driven at least 680 vertebrate species to extinction since 1500.’

Amphibians: ‘More than 40% of amphibian species are currently threatened.’

Insects: ‘Global trends in insect populations are not known but rapid declines have been well documented’ ‘tentative estimate of 10% threatened by extinction.’

The overall summary looks very sombre

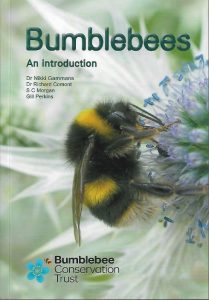

Bumblebees (BCT) – a review

Bumblebees, An Introduction. By Nikki Gammans, Richard Comont, S.C. Morgan and Gill Perkins. Bumblebee Conservation Trust. 2018. 174pp.

Edited by four bumblebee experts, this is a major work from eight contributors including the editors. Put together by the Bumblebee Conservation Trust (BCT) it does what ‘it says on the tin’, it is a great introduction, possibly the best introduction to these appealing insects for the general public. The book is extensively illustrated in colour throughout, including the works of 18 photographers including those of entomologist Steven Falk. This book presents a bewildering array of imagery that maps all the finer points of bumblebee biology that make identification easier. The book has seven chapters: introduction, pollination, decline, gardens, collecting, ‘the big seven’ (buff-tailed, white-tailed, red-tailed, common carder, early, tree and heath) and the major chapter on Identification. Bumblebees are here classified into four groups, red tails, ginger tails, yellow tails and cuckoo bees, a refreshing classification that departs from earlier books, but very effect. Each of the 24 extant species of bumblebee (three have already gone extinct) is clearly shown as colour bar diagrams of body bands, photographs in the wild showing particular characteristics (noted and shown on the photographs), life cycle through the months and a distribution map. This is a very exciting compilation and will be a great success for BCT. The book will be thumbed through by eager entomologists, hymenopterists and amateur naturalists – it is small enough to go into a field jacket or knapsack for identification and it has a glossary, index and further information.