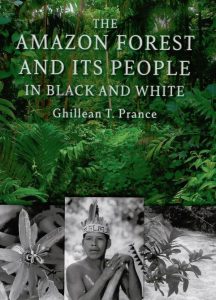

Ghillean T. Prance, 2022. The Amazon Forest and Its People in Black and White. Published by ‘Butterflies and Amazonia’. ISBN: 978-1-7398856-2-5. £20. Marketed by Redfern Natural History Productions Limited, at https://www.redfernnaturalhistory.com/product/amazon-forest/

Before Prof. Prance became Director of The Royal Botanic Garden, Kew (1988-1999) he spent years in the Amazonian Basin tirelessly cataloguing the botany and describing new species to science, but that was when he was working for the New York Botanic Garden (1964-1988) and nipped off to the rainforest on 39 expeditions as one does. Few have ever had the extensive tropical field work that Prance has had, resulting in the discovery of 350 new species of plants especially with his exploration of the Serra Aracá plateau.

This book is all about then, but is a salutary lesson about now. In this book you feel the warmth of the Amazonian people living sustainably off this watery world, whilst we in the West look in wonder and try to interpret how their way of life revolves around their natural habitats, flora and fauna. In my experience the further you get away from civilisation the nicer and more helpful people are. This is reflected in the pages.

So this book looks at the nature of the living world that shapes the way of life of the Amazonian people, from their buildings made of wood and palm leaves, their ceramic clay pans, calabash cups, their baskets, red dye plants, natural fruits of the forest, ‘water vines’, plants to stun fish and plants used as contraceptives. No wonder the intrepid botanist Prance edited the more recent Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs (2018) – this is just one of the 29 books that he has written; Sir Ghillean’s knowledge is wide and wise and he has a genus Pranceacanthus named after him.

Prance has trekked and waded through the Amazon rainforests where only a few famous people before him have ventured, including President Roosevelt and his son, as well as Victorian naturalists Henry Bates, Richard Spruce and Alfred Russel Wallace – probably more time in the forest than the Victorians. Prance confirms to me that he has certainly spent more time in the Amazon rainforest than Wallace and Bates, and at least the same time as Spruce. The longest continuous period he was there was two and a half years in 1973-1976.

Prof. Prance experienced the Amazonian rainforest as he says: ‘When I first went to the Amazon…..I saw many of the same things as the Victorian naturalists’. ‘There was comparatively little destruction of the forest’ then. The photographs in the book are backed up with quotations from many of these early explorers indicating how untroubled the habitats were from man. Darwin had a short spell near Rio but never penetrated the Amazon.

Prance’s botanical skill and knowledge shines through with his descriptions of trees and vines and his identification of all the plants that the Amazonian people use for their life in the forest, and the ‘fruits of the forest’ that they depend on. This includes the ‘Siokoniamo’ fungus (Lentinus velutinus) which translates as the ‘hairy arse fungus’.

The chapter on the giant Victorian Water lily is delightful, as a species that can block a waterway with its magnificence (other lesser plants do too), its structurally-sound leaves that man has copied in architecture, and the way it captures beetles overnight for pollination purposes. He introduces us to various Amazonian tribes, the Yanomami, Mayongong, Tikuna, Huitoro, the Jarawara, the Deni and the river people (the caboclo) who all visitors to the Amazon will meet. This book records much of their social history with plants.

At school in England they never tell you that the water level of the Amazon rises and falls dramatically each year by several metres, which alters the nature of habitats; or that there are many of these caboclo people of African and European ancestry who live along these fertile waters who are not the tribes. Of the native Indians there used to be over 2-6 million present (of over 350-400 tribes) before the Europeans arrived in the late 15th century, and, as the cataloguer Greta Thunberg says, 90% of the Indigenous people were either massacred or died of infectious diseases, or 10% of the world population (see previous review of Thunberg’s latest book). This is their assimilation with the forest.

Although the botany of the Amazon has not changed since it was photographed in black and white in the 1970-80s, there has been much destruction. Prance’s photo of rubber balls waiting for trading is almost a thing of the past, and the rubber industry that he describes had such a traumatic effect on the people, at the hands of the rubber barons who created the incongruous Opera House in Manaus.

Throughout the book and alongside photographs there are paragraphs from the Victorian explorers Bates, Spruce, Wallace and others and it is very telling that the population of Manaus in 1850 was just 3000 people. Now it is a major hub for exploration of the Amazon with a population of over two million people. The book has a botanical slant for obvious reasons, but animals photographed in black and white are included. Feathers and furs are still used for adornment. Sadly society still collects wildlife and this reviewer’s first encounter with a wild jaguar was in a cage display in a hotel’s foyer, not in its natural habitat.

Of the way that things have moved on, I liked the understatement that oil palm ‘as much planted by locals and also as an industrial crop that is destroying some rainforest areas especially in Amazonian Peru and tropical Asia’. Too true. You can fly for an hour or so along the Pacific Central American rainforest and see plantations of oil seed palm to the horizon that has replaced rainforest and all its biodiversity.

I am very glad that Sir Ghillean Prance still refers to ‘rainforest’ (it is all in the name), as opposed to David Attenborough who refers to it as ‘jungle’ (dry, spiny tropical forest). All books on the Amazon are a lesson to us all. The tropical habitat continues to be systematically destroyed. Prance is ever hopeful for a suitable outcome, for he says ‘It is not too late to help’ and he calls on Davi Kopenawa from the Yanomami tribe who asks whether the white people know that when they kill ‘the spirits of the big earthworms (who) own the forest earth’, that the soil will instantly become arid.

Overall, this is beautiful book that demonstrates the way that indigenous people are at peace with their environment. There is a glossary, index and further information on charities that readers can help with rainforest conservation, and a list of publications of the early explorers cited.