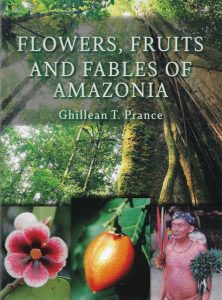

Flowers, Fruits and Fables of Amazonia, published by Redfern Natural History Productions (www.redfernnaturalhistory.com) in 2023, by Ghilliean T. Prance. 298pp. ISBN 978-1-908787-46-0.

Biodiversity runs riot in this book, which is full of the some of the most colourful plants in the world, those from Amazonia, written by one who has been their most, Sir Ghillean Prance, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew (1988-1999) and has mounted 39 expeditions to all the wet and dry, lowland and highland habitats there, and bringing back 350 new species of plant for science.

It may be a colourful book but there is a sombre message, for the book is dedicated to the President of Brazil and to Ministers Marina Silva and Sonia Guajajara ‘in the hope that they can halt the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest and use it sustainably.’

As befits a Director of Kew the book is laid out in a strictly classificatory manner, pteridophytes, gymnosperms, monocots and dicots which is very useful if your thought processes are botanically inclined. Grasses, which include bamboos, are described even though they have limited colourful appeal, they are big colonisers of the backwaters of Amazonia – many a time our way has been blocked by wild rices which we have had to powerboat–over. On terra firma ones way is often thwarted by stands of dense bamboo. Where plants have been taxonomically split with new up to date DNA evidence these are explained in good order.

So this is a very colourful book because of the chosen subjects, and we must remember that the colours have evolved because of the pollinators, the insects, other invertebrates, birds and bats. All of these are mentioned in the text, some of them seen doing their bit for pollination, squeezing and nudging blossoms to get their reciprocal rewards. The colourful flowers would not be so diverse if it was not without this co-evolution with insects. We see the change in floral colours after pollination.

This intimate evolution of plant morphology has not been missed by those who puzzle over the Doctrine of Signatures, particular the Clitonia genus, and Prance recalls the squeamishness of the early taxonomists as to how to describe these female features in a flower. If that was not enough, in Europe the look-alike Fallopian tubes of Aristolochia clematitis are also fair and square examples of the doctrine, mirrored also by other much larger tube-like Aristolochia species in Amazonia.

Prof Prances’ firm favourite in the forest is the native Brazil-nut family (Lecythidaceae) – his group – on which he has researched much with his late colleague Dr Scott Mori (d. 2020) fellow researcher at NY Botanic Garden – there are 340 species in the family. The family includes the Cannon-ball tree and the Brazil nut tree. Both are large unforgettable distinguished trees in the rainforest – just visit the Rio Botanic Garden to see many tree treats described in this book. Prance describes the Brazil nut tree as the ‘most beautiful tree of the Amazonian forest’; the tree was named after a most beautiful young woman of the Tefé Indians called Caboré, who was mysteriously lost in the forest and came back as a valuable forest tree that brought livelihood and food for the community.

There are many other fables described in this book, true to the books’ title, and they are highlighted in pale green throughout to distinguish it from the main text. The rainforest is actually an unforgiving environment for man, and many of the fables relate to death of revered ones; a long story of Naia who drowned when trying to kiss her lover (the moon) and came back as a giant Victoria water lily (three species, with the largest undivided leaves in the world at 2m diameter); the white-skinned Tupi girl called Mani who became ill and came back as a root of cassava or manihot, the word coming from a combination of two Tupi words Mani and oca; a long story of the Bacaba palm sprouting at the top of a hill from one lost in battle.

There are a lot of red flowers and fruits illustrated in the book, but then these are multi-purpose colours for advertisement pollinators, signals to fruit eaters for dispersal purposes, and warning colours. The asymmetrical red, black ad white seeds of the guaraná plant arose from the buried eyes of a boy killed by a snake.

In this book we therefore get an insight into the peoples of the forest, the Yanomami preparing the hallucinogenic snuff from the Virola tree, Bixa body paint, the Jarawara snorting tobacco, the weaving of baskets, utensils, woodworking skills for canoes and houses, extracting curare as an arrow poison, and making chewing gum from latex (really puts Prance off it for life). There are medicinal uses, including covering sick babies with Genipapo paint.

The book would appeal to all naturalists and students of tropical ecology, and those who have never visited a tropical forest. It would also appeal to all those who have visited tropical botanic gardens around the world, since there are some familiar examples that are neotropical or pantropical as described in the book. Others who would benefit from this book would include those who have been on any Latin American tropical field trip. There is an index, scientific and common names indexes and a list of papers from which evidence has been drawn, including just a few of the author’s 590 scientific papers. A fine read and colourful window into the leafy heart of Amazonia.