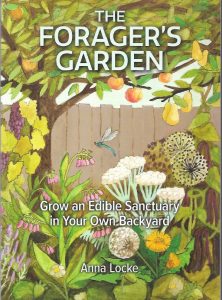

The Forager’s Garden, Grow an Edible Sanctuary in Your Own Backyard. By Anna Locke. Permanent Publications. 2021. 194pp. £9.95 RRP. ISBN 978-1-85623307-1 9 781856233071

The author has a herbal medicine degree and is an expert on permaculture and has produced a fine example of an easily accessible book for beginners to grow food. The book is not about foraging about along waysides and woodlands to bring back bunches of edible plants a la Richard Mabey’s ‘Food For Free’. It is more about a wake up call to bring useful plants into the garden and let them perform, or run riot; or let them arise and colonise the garden, in a form of rewilding. Rewilding is one of three principles of permaculture and there is a small section in this book but that subject is covered elsewhere in Isabella Tree’s book on ‘Wilding’ as a different kind of feeding off the land. However, amongst the many colour photographs, and black and white artworks, there are plenty of ‘wild’ looking parts of the garden up against walls, gravelly edges, which is just what Anna proposes, willowherbs, foxgloves, apples, pears and plenty of ground cover, no neat lawns here. There are 15 chapters which range from wildflowers, trees, and managing the wild garden, composting, pruning and being at ease with the space; and lists and tables to consider on species selection. There are also plenty of plans for layout in small places, but the ideas can go large to fit most spaces and enthusiasms. The author’s experience of a garden designer in London brings a lot of professionism to the book, and common sense for which beginners will be grateful. There are some neat tricks for water collection and distribution for off-grid gardens, reminding me of ideas that might be found in the alternative energy site in Wales, or in drought years, or in the Mediterranean (Anna has inspiration from Sicily). Anna Locke practices in Hastings and manages the Ore in Bloom society. There are references to local places such as the Hornsburst Wood Forest Garden and the Bohemia Walled Garden Association which show, with before and after images, how gardens can be turned round to being useful for food production. But the wild turnaround can be applied anywhere. The book is for the UK and US market and the species chosen and all the ideas are applicable both sides of the Atlantic. I like Anna’s enthusiasm for plant guilds that naturalists would also call suites of species, or just an example of rich biodiversity where in nature everything grows together. Bringing associated species together in gardens (for instance with plug plants), or just encouraging them to find their place and spread naturally, is presumably an aim for any wild garden, except here there is a preference for food. There is no need to eat the foxgloves (steady on there – danger!) but daisies, bugle and sorrel are recommended as food. Clearly Anna likes nature, and her acknowledgement ‘To the field that held me’ reminds me of Robert Louis Stevenson who so liked the woodlands on his camping trek through the Cevennes mountains, that in the morning he laid coins on tree stumps as a thank you for such a nice environment. I too, know that feeling. Give me a wood or meadow any day. For those beginners who get inspired by this book, they can save themselves a lot of money by foraging in their own back yard. This book also ticks the principle boxes for ‘regenerative agriculture’ and ‘community resilience’. If you have a very large back yard you could at least have some wild boar to do some of the hard digging for you. The book is recommended for all those would would like to live the foraging life and commune with nature.