Wilding, the return of nature to a British farm. Isabella Tree. London, Picador. Paperback edition 2018. 363pp.

Rewilding is the common parlance for ‘Wilding’. As the author says wilding ‘is restoration by letting go’ (p.8), and that the stubborn ‘re-‘ reveals a naïve ambition to recover the past (p.152). The farm dropped the ‘re’ to concentrate on a ‘long term, minimum intervention, natural process-led’ operation (p.160). And a great success it has been. Knepp is synonymous with rewilding.

The sub-title is an understatement. The British farm in West Sussex is no ordinary farm, it is 3,500ac with a castle (and lost town) that was visited by King John in 1201. The book is about how the farm changed from being a reasonable profitable dairy and arable farm (though unsustainable p.39) to a farm for nature conservation over the last, now twenty years. It is written by one of the co-owners of the farm with her partner Charlie Burrell and is essentially the modern history of Knepp. And what a struggle it has been.

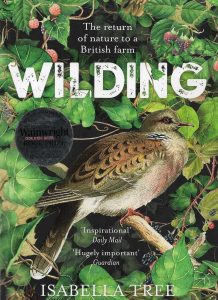

There are seventeen chapters, some of them about single species, such as beavers, nightingales, purple emperors and turtle doves – in a sense the book could have been dedicated to the turtle dove (on the book cover) because all the conservation ‘strategy’ had led up to optimal habitat for this species, and for nightingales, purple emperors and many other invertebrates too including plenty of BAP species. There can be few wild areas spread about Britain that are becoming refuges for wildlife, but this is one of them.

The change from intensive farming to farming for nature conservation took at least ten years for an income stream to materialise. The Countryside Stewardship Scheme agreement funded the management of part of the estate from 2000-2010, and the Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) chipped in for another 10 years from 1 January 2010 (p.175). This is what used to be called ‘being paid not farm’, which is not the case here, and where there was the perverse situation of EU giving grants to farm intensively and grants to reverse the effects of farming intensively. By 2010 they had 283 Longhorn cattle ‘a by-product of rewilding began to present itself as a potentially significant income stream’ (p.246) without any need to feed or pay for fences, sheds etc and few veterinary costs.

There were plenty of critics of the Knepp Wildland Project from locals, professionals and statutory bodies who could not get their heads around the concept of wilding. Natural England gave Isabella a run-around for at least 10 years. The concept was completely alien to NE – it did not fit with their modus operandi – which cannot operate without evidential information about wilding to inform any engagement with Knepp – or as Keith Kirby of NE said it was a project without ‘sound scientific base for what is proposed’ (p.93). So it was a NO from NE, even though NE had been involved with the ‘Wild Ennerdale’ project in the Lake District in 2003. Surprise, surprise. The decline from NE was even after a site visit to see the hugely successful recreated grasslands and wetlands of the Oostvaardersplassen in the Netherlands created on a reclaimed polder. In her attempt to rewild 1.5miles of the River Adur that flows through the property it had taken 16 years of failure (up to 2017 publication) to get a grant from the many authorities, which she states as shameful (p.229). The aerial colour photographs show it all. A huge success.

The book is incredibly well researched with scientific papers per chapter quoted at the back. There is a sublime chapter on scrub which is probably not seen in any other book. The author goes to great length to present all the background information on the subject before getting to the subject in hand – but it still presents a good read, a crammer for some of the species subjects, whether it is pigs, cattle or deer. Overall she is very frustrated at the slowness of authorities to accept rewilding, but then it goes against all conservative conservation strategies that are not based on abandonment of habitats. However, the author is delighted about the wildlife fruits of the venture in the mosaic of habitats created and the clamour of wildlife to inhabit it, in some cases the best populations of animals in the southern England – for instance maybe the only place in Britain where turtle dove numbers have increased: Sussex has 200 of the 5000 pairs in Britain (p.194) and Knepp possibly has the greatest density of bird surviving in England (p. 201). Autecological information gleaned from the Knepp estate about turtle doves allowed them to decline the local ‘Operation Turtle Dove’ project proposed by NE in 2012 and the author sadly called it a case of ‘the principle failings of conventional conservation’. (p.200) Altogether it is an absorbing good read and all ecologists, naturalists and anyone interested in nature should read the book. A one off.