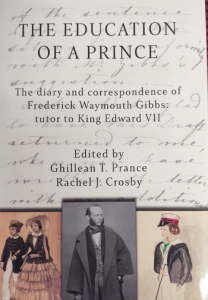

The Education of a Prince, The Diary and correspondence of Frederick Waymouth Gibbs: tutor to King Edward VII. Edited by Ghillean T. Prance and Rachel J. Crosby. 2024. pp141. ISBN 978-1-908787-50-7 and ISBN 9 781908 787507.

The papers of Mr. Gibbs (1821-1898), including his diary, letters and prints have come directly down the family tree to these two authors, Prof. Sir Ghillean T. Prance (Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew from 1988 to 1999) and his daughter (manager of international projects in Africa and South America), Frederick Gibbs being Prance’s second cousin of his grandfather. Gibbs’ claim to fame was that he was the tutor to Queen Victoria’s two eldest sons, from 1851-1856, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, and Prince Alfred.

And what a hard life Gibbs seems to have had. It was not an easy teaching job, since the Prince of Wales was particularly truculent, aggressive and prone to throwing things around. These transcripts of diary entries and letters (some originals are shown written in a spidery quill hand) are revealing and deal mostly with everyday life in royal Victorian circles. Most of the political issues of the day are not included. There are timetables and strict work schedules, often metered out by Victoria who insisted on seven hours teaching, sometimes seven days a week especially if the princes were especially naughty. There were many “wishes of the Queen on a number of small points and generally the host of nothings which become important only when neglected” said Gibbs in a letter home from Windsor Castle in 1852. There were “Rules for Meals” and regulations, such as not being rude to their sisters, how not to fidget with cutlery at the table, and never to interrupt people speaking at mealtimes, and when precisely to wear a kilt. The Queen also provided approved lists of suitable boys (17 are listed) who the Prince of Wales could have round to play during the summer – and eight listed for Prince Alfred. Eton, being next door to Windsor Castle had been a source of teachers and appropriate playmates.

Day to day entries in his diaries are sometimes like entries in a school report…”the impulse to oppose is very strong and offers great difficulties in his education”, and “nothing makes a deep impression, and he forgets the greatest part of what he learns”… It seems hard work for Mr. Gibbs considering all the non-cooperation he had with the Prince of Wales, all for an annual fee of £1,000. He took over from a master at Eton who was regarded as being too lenient with the boys, which is why the Queen wanted someone a little more stricter. This did not go down well with the boys so Gibbs took a while to settle in. The diaries show that Victoria gave him presents, and that he dined with her on some evenings. In his role as a teacher he had to work at Buckingham Palace, Osborne House and Sandringham and took voyages around the coast following his subjects. In 1852 the Queen had a phrenologist look at the princes’ heads to see if they were developing correctly. “The predominant organs are still combativeness, destructiveness, self-esteem, firmness and conscistiousness. Concentrativeness also is large, and the cerebellum is of considerable size having increased since May 1851.” Phrenology was highly regarded at the time.

The book is illustrated with very good sketches from Albert Edward, and black and white photographs of the boys later in life, and Queen Victoria. There is correspondence between the princes after Gibbs left when he continued to write to them, and received letters from them with presents, and others, including Tennyson residing at Henley on Thames. He was given £400 rising to £800 for his pension after four years.

The book provides a valuable insight into royal life during this snapshot of Victoria’s life. The entries will provide historians with a wealth of finer detail from ‘upstairs’ as seen by a teacher, as well as shining a light on the abundance of courtesy, etiquette and behaviour amongst the royals. As a teacher Gibbs clearly earnt his keep within the household and the princes obviously appreciated his efforts as they continued to send him presents during his retirement; so did the Queen. This was not an ordinary life of a teacher, but a privileged one.