The Lost Paths – A history of How We Walk from Here to There. By Jack Cornish. Penguin Michael Joseph, London. Hardback. £20. 399pp. 2024

The author is ‘Head of Paths at the Ramblers, Britain’s largest walking charity’ so says the cover blurb, and he packs a lot into this very readable and enjoyable book. He has walked across Britain from Land’s End to John O’Groats, and spent seven years researching this book and walking all over England and Wales. There are a dozen chapters broken down to three sections: Land, Life and death and Water with relevant road issues dropping into each section. We are advised that when the Romans arrived there were already main paths or tracks, which are mentioned in his ‘Ancient Highways’ and his ‘Prehistoric Routes’ – often following animal routes – ‘wild animals were the first path makers’. (They still are in wilder parts of France – a JF comment: made by solitaire male wild boars). He peppers his text with his first- hand accounts of his walks, for instance finding the lost roads above Sheffield and on the Moors; or on Drove Roads. On Roman roads he says ‘It could be said that their (Roman) roads are the Archetypical lost paths.’ His sections on how turnpikes came about and local labour was used, how the railway infrastructure and the Enclosures changed things are all explained, in this circuitous country. Of the Salt Ways he creates an interesting salt map in north England. His section on battlefield routes is fascinating and he says the state of the roads must have been good for Harold and his men to cover the 200 miles for the Battle of Hastings in four and half days. Of the eroding coasts and loss of walkways, he speaks so well from experience trying to carry on walking when the (OS) route on the map does not equate to the way ahead. What is so good about the text is that it is interwoven with quotes from English literature. I was fascinated to learn that William Wordsworth was such an agitator against landowners blocking up footpaths (when he visited Lowther Castle in 1836 tossing rocks from a deliberate obstruction). Fast forward to the ‘scum of the earth’ ramblers case in 1998 of ESCC vs. Van Hoogstraten is described. This is definitely a good read for all walkers and ramblers; and a good book just to dip into. The text is packed with fascinating information and there is a comprehensive index and plenty of references to explore further texts. The author does not let any side comments pass, and his long footnotes are fascinating in themselves. As an author I know that it is difficult to not include lots and lots of information, and in this well-researched book it shows in its comprehensiveness. Footnote: ‘The Saxons gave a lot to our naming of paths’: the word ‘way’ comes from the Anglo-Saxon ‘weg’.

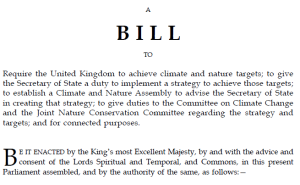

Climate and Nature Bill (2024) The ‘CAN’ Bill

(Briefing Note from Dr John Feltwell, Dip EC Law of Wildlife Matters . 5 Jan 25)

Summary – the Bill seeks

- To limit the global mean temperature increase to 1.5 degrees C

- To ‘visibly and measurably’ see species and habitats ‘on the path of recovery’, to be measured from 2020-2030.

- To abide by the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement,

- To abide Leaders’ Pledge for Nature, 2020

- To abide by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, 2022

- To abide by the UNCBD and its protocols , 1993.

The Bill

This Private Members’ Bill was presented to parliament by Alex Sobel on 21 March 2024 and supported by a dozen MPs, mostly Labour, Lib Dems and Green Party –that included notables Caroline Lucas and Ed Davey.

Progress through The House

The Second Reading is scheduled to take place on 24 Jan 2025.

The official ‘Long Title’ is

A Bill to require the United Kingdom to achieve climate and nature targets; to give the Secretary of State a duty to implement a strategy to achieve those targets; to establish a Climate and Nature Assembly to advise the Secretary of State in creating that strategy; to give duties to the Committee on Climate Change and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee regarding the strategy and targets; and for connected purposes.

It has two OBJECTIVES – to ensure that the UK

(a) reduces its overall contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions to net zero at a rate consistent with—

(i) limiting the global mean temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels as defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; and

- ii) fulfilling its obligations and commitments under the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, taking into account the United Kingdom’s and other countries’ common but differentiated responsibilities, and respective capabilities, considering national circumstances; (‘the climate target’); and

(b) halts and reverses its overall contribution to the degradation and loss of nature in the United Kingdom and overseas by—

(i) increasing the health, abundance, diversity and resilience of species, populations, habitats and ecosystems so that by 2030, and measured against a baseline of 2020, nature is visibly and measurably on the path of recovery;

- ii) fulfilling its obligations under the UNCBD and its protocols and the commitments set out in the Leaders’ Pledge for Nature 58/4 5 10 15 20 Bill 192 2 Climate and Nature Bill and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework; and

(iii) following the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities; (‘the nature target’).

The Bill has the following definitions of ‘nature’ as

“nature” includes— (a) the abundance, diversity and distribution of animal, plant, fungal and microbial life, (b) (c) the extent and condition of habitats, and the health and integrity of ecosystems;

And the definition of ‘ecosystems’ as

“ecosystems” includes natural and managed ecosystems and the air, soils, water and abundance and diversity of organisms of which they are composed.

Biodiversity – one big ask

Most of the Bill is about C02, but on Biodiversity there is not so much, only the following statement, and a request to abide by previous pieces of biodiversity legislation

Restoring and expanding natural ecosystems and enhancing the management of cultivated ecosystems, in the United Kingdom and overseas, to protect and enhance biodiversity, ecological processes, and ecosystem service provision;

The three previous biodiversity commitments are:

- fulfilling its obligations under the UNCBD and its protocols and the commitments set out in the Leaders’ Pledge for Nature 58/4 5 10 15 20 Bill 192 2 Climate and Nature Bill and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework; and

Unpicking this statement, there are three biodiversity legal issues:

- “the Leaders’ Pledge for Nature” means the agreement of the United Nations Summit on Biodiversity of 28 September 2020; and

- “the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” means the framework adopted by the decision of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in Montreal on 19 December 2022; and “the Mitigation and Conservation Hierarchy” means the hierarchy adopted by resolution 58 of the World Conservation Congress at the International Union for Conservation of Nature from 1 to 10 September 2016. and

- “UNCBD and its protocols” means the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, which entered into force on 29 December 1993, and all subsequent agreements and protocols arising from it;

Overall Comment

If all of these recommendations and commitments are upheld the steady plod of the Anthropocene will be stopped, C02 levels curtailed, and everything will be fine. However, history tells us that even after 30 years the 1993 initiatives have not been followed which is why the Anthropocene is upon us.

How will the Climate and Nature Bill fit into local politics?

If enacted, the Act will require Rother District Council to abide (especially) by the paragraph highlighted in red above, and their own declaration of the Climate Emergency in 2019. They only have five years from NOW.

Dr John Feltwell, BSc (Hons Zoology), PhD (Botany), FLS, FRES, FRSB, FLLA, Dip EC Law, Henley’s Down, Battle, TN33 9BN. 07793 006832 john@wildlifematters.com www.wildlifematters.com

ends